What Are Fine Art Prints? Guide to Screenprinting, Woodcuts, Etching & Lithography

Beginner’s Guide to Prints and Multiples: What Matters Most

Understanding What a Print Is

A print is a piece of art made through a process that lets the artist create more than one version. Instead of drawing or painting each one by hand, the image is transferred from one surface to another. This is what makes prints different from paintings or drawings. Some of the most common printmaking methods are etching, lithography, screen printing, and woodcut. Each one has its own tools, steps, and effects.

What Makes Etching Unique

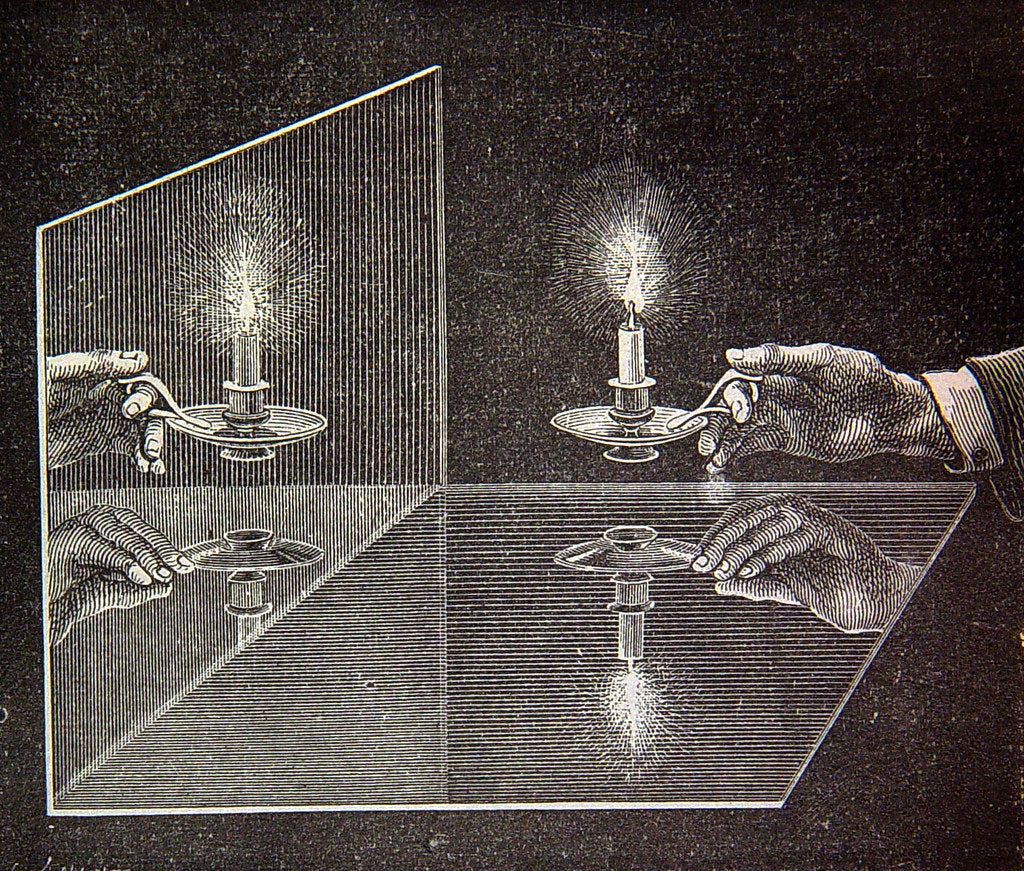

Etching is done using a metal plate, usually covered with a wax coating. The artist takes a sharp tool and scratches a design into the wax. This reveals the metal underneath. Then the plate gets soaked in acid. The acid bites into the exposed lines, and the longer it sits, the deeper the grooves get. That changes how dark the lines will be when printed.

Once the acid has done its job, the plate gets cleaned. Then it’s inked and wiped again so that only the etched lines hold ink. Wet paper goes over the plate, followed by a layer of cloth. The whole thing runs through a heavy press. The pressure pushes the paper into the grooves and lifts out the ink.

The result is a mirror image of the original drawing. You can often spot an etching by the faint outline left by the plate's edges. This is called the plate mark.

Artists have been using this method for centuries to create fine black and white prints. Rembrandt used etching to build moody, detailed scenes. In more recent times, Lucian Freud used it too, continuing the tradition in a modern style.

How Lithography Works

Lithography is a very different process. Instead of scratching into metal, the artist draws directly on a smooth stone surface using something greasy like a crayon or oily ink called tusche. Then, a chemical treatment is applied to the stone. This locks in the drawn areas and makes sure the blank areas only attract water, not ink.

Next, the stone is dampened with water and rolled with oil-based ink. The ink sticks only to the greasy drawing and not to the wet parts. Then a sheet of damp paper is placed on the stone, along with a board to spread the pressure. A press pushes everything together evenly, and the image transfers in reverse.

For prints with more than one color, a separate stone is used for each layer. This process can take time, but allows for rich, layered images.

Lithography made printmaking easier for artists who didn’t want to master harder techniques like woodcut or etching. Since it uses tools like pencils and brushes, it feels more natural to many painters. The method became popular in the 1800s, thanks to artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. In the 20th century, big names like Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, David Hockney, and Jasper Johns all used lithography to make some of their best-known works.

The Value of Prints and Multiples

What makes prints so interesting is that they’re originals, even if there’s more than one. These aren’t copies made later. Each print in a limited edition was part of the artist’s process from the start. That gives them real value.

Collectors pay close attention to edition size, paper quality, and condition. The smaller the edition, the rarer each print becomes. High-end prints are often on handmade or fine archival paper. That matters a lot when it comes to long-term quality and price.

Understanding the method used (etching, lithography, or another) also helps collectors figure out how the artist worked and what kind of result to expect. Different methods create different textures and lines. Each one has a look and feel that adds to the story of the piece.

Printmaking has always been a mix of craft and creativity. It’s about process, tools, and materials, but also about choice. Knowing how a print is made gives you a deeper appreciation of the work and helps you make smarter decisions when collecting.

How Screenprinting Works in Fine Art

Screenprinting, also called silkscreen or serigraphy, is a hands-on printmaking method that uses stencils to control where ink goes on paper. To start, an image is either drawn or cut into a thin sheet of paper or plastic film. This sheet becomes a stencil. The stencil gets placed on a frame that has a tight mesh screen stretched over it. This screen acts like a filter for the ink.

A clean sheet of paper is set below the screen. Then, ink is poured on top. A rubber blade, called a squeegee, is dragged across the screen. The ink only pushes through the cut-out areas of the stencil. The rest of the mesh blocks it. This is how the image gets printed onto the paper in clean, bold shapes.

Screenprinting isn’t limited to hand-cut stencils. Artists can also use a process that applies a photographic image to the screen using light-sensitive emulsions. This approach lets them transfer detailed photos, text, or drawings directly onto the mesh. The exposure process hardens parts of the emulsion and washes away the rest, creating a precise stencil from a photo or digital image.

This innovation had a huge impact on Pop artists like Andy Warhol. He used it to print images of celebrities, logos, and everyday consumer goods, often repeating them in grids or vibrant colors. This method let him take commercial images and turn them into something both familiar and new. Warhol’s screenprints of Marilyn Monroe and Campbell’s soup cans wouldn’t have been possible without this blend of manual and photographic techniques.

Screenprinting makes it easy to experiment with layers, color changes, and repetition. That’s why it’s still popular with contemporary artists who want sharp, flat color and graphic impact. Each color is usually printed one at a time, so multi-color prints require multiple screens and perfect alignment. Even with this technical side, screenprinting remains one of the most flexible methods in modern printmaking.

The Process and Power of Woodcut

Woodcut is the oldest known method of making prints. The process starts with a flat block of wood. The artist sketches an image directly onto the surface. Then, using knives and gouges, they carve away the parts of the design they want to stay white. What’s left behind are the raised parts that will hold the ink.

Once the carving is done, ink is rolled over the surface using a brayer. Because the carved-out parts sit lower, they don’t catch any ink. A sheet of paper is laid over the inked block, and pressure is applied, either by hand or with a press. This pressure transfers the image to the paper, but flipped in reverse.

Every print in a woodcut edition carries the rough texture and lines of the carved wood. The grain of the block often shows through, giving it a raw and tactile quality. No two prints are perfectly identical, even in the same edition.

Woodcut prints were a major part of early book illustration in Asia and Europe, but artists kept using the method for its bold, expressive power. German Expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner brought it into the 20th century with striking black lines and emotional force. Their prints weren’t just about technique. They were about mood, energy, and raw human expression.

More recently, artists like Donald Judd, Damien Hirst, and Helen Frankenthaler have brought fresh eyes to the process. Some focus on shape and color. Others push the limits by layering or combining woodcut with other print methods. Even with new tools and technologies, woodcut still holds its place for artists who want a direct, physical connection with their materials.

Why Prints Are Original Works, Not Just Copies

A lot of people think prints are just cheaper copies of a real artwork. But in fine art, that’s not true at all. A print isn’t just a reproduction. It’s an original work made through a unique process. The artist works closely with a print studio or master printer to create the final piece.

The person who runs the press isn’t just pushing buttons. They’re trained in every part of the method. They know how ink reacts, how paper absorbs it, how much pressure to use, and how to line things up perfectly. Many are artists themselves. Without their skills, the artist’s vision wouldn’t come out the same way.

Fine art prints aren’t mass-produced. They come in limited editions, often signed and numbered by the artist. Once that edition is complete, no more are made from the same plate or screen. This limit gives each print a real place in the artist’s body of work.

Prints are sold through trusted channels: directly from the artist, through galleries, or with the help of publishers who specialize in fine art editions. They’re not factory products. They’re created with just as much care as a drawing or painting. A print might be one of several, but each one is still an original that holds artistic value.

Why Artists Create Prints: Creative Freedom, Process, and Access

Artists turn to printmaking for many different reasons. Some are drawn to the technical side. Others like how it lets them explore fresh ideas or rethink older ones. For many, prints are more than just copies. They’re a direct extension of their main studio practice, but with a different set of tools and rules.

One major reason artists make prints is the process itself. Printmaking often takes place in a dedicated workshop or print studio. These spaces are usually run by skilled printers who work closely with the artist. That collaboration is key. It’s not just someone helping run the press. The printer becomes a partner in shaping the final image. The back-and-forth between artist and printer can open up creative paths that might not happen in the artist’s solo practice.

Printmaking also offers a chance to experiment. The materials, the steps, the repetition - all of it invites the artist to slow down and reconsider. Each stage matters. Every decision is locked in and re-evaluated as the print develops. This step-by-step approach can reveal new things about an artist’s ideas. Sometimes, working in prints helps an artist break through a creative block or figure out problems they couldn’t solve in another medium.

Some artists use printmaking as a way to switch gears. It becomes a separate part of their practice. Lucian Freud is one clear example. After spending the day painting in oils, he would switch to etching in black and white. It gave him a different rhythm. No color. No brushwork. Just line, pressure, and form. These prints weren't side projects. They were a direct reflection of his vision, filtered through another medium.

On the other hand, Ellsworth Kelly applied the same strict sense of shape and color to both his paintings and his prints. For him, the medium didn’t change the message. The form and color still took center stage, but working in editions gave him another way to sharpen those elements and bring them to new audiences.

Some artists work in prints consistently, year after year. Jasper Johns is one. He returned to printmaking throughout his long career, often revisiting symbols and themes in different ways. Pablo Picasso is another. He made hundreds of prints across every major print method, from linocuts to lithographs to etchings. For them, prints were just as serious and important as their paintings or sculptures.

Other artists, like Barnett Newman, didn’t always make prints. They came to printmaking in specific periods, often tied to a certain print studio or workshop. In these moments, the switch to print was intentional. It marked a break in their routine or a chance to explore something new with the help of a skilled technical team. Those brief windows often produced some of their most focused and unique work.

Original Prints vs. Editions and Multiples: What Really Matters

What an Original Print Actually Means

In printmaking, the word original doesn't mean the same thing it does with paintings or drawings. A painting is one-of-a-kind by nature. A print, on the other hand, is made with the idea of creating several finished pieces from a single plate, block, screen, or stone. Still, each print in that set can be considered an original as long as the artist directly took part in its creation and approved the final image.

An original print is not a reproduction. It isn’t a photocopy or a digital replica of an existing artwork. Instead, it’s a planned and executed artwork in print form, made as part of a limited edition. The artist either physically worked on the surface that created the image or oversaw the printing process themselves. This makes each impression an authentic part of the artist’s output.

How Editions Are Marked and Why the Numbers Matter

When an artist releases a print as part of an edition, each individual piece is numbered. These numbers appear as fractions. For example, a print marked 5/30 tells you two things: first, that it’s the fifth print made in that run, and second, that there are thirty prints total in the edition.

Edition numbers are important because they affect value, rarity, and collector interest. Smaller editions usually carry more value because fewer copies exist. A print from an edition of 15 will likely be seen as more desirable than one from a run of 200, all other things being equal.

That said, the number itself doesn’t always reflect the order in which it was printed. Print 2/30 wasn’t necessarily pulled before print 29/30. The numbering is more about identification than sequence.

Artist’s Proofs and Their Role in the Market

Apart from the standard numbered edition, artists often create a handful of artist’s proofs, usually labeled as A/P. These are nearly always identical in quality and appearance to the standard edition prints, but they aren’t counted in the official edition size.

So if you see A/P 1/4, that means it’s the first of four artist’s proofs made. Collectors often seek these out. Even though they look the same as the edition prints, they’re sometimes considered a little more special because they were set aside by the artist, either for personal use or for close collaborators.

Artist’s proofs can fetch higher prices, especially if the edition is sold out or if the artist is well-known. Their limited number and the direct connection to the artist’s hand make them more desirable to some buyers.

Other Types of Proofs: Trial, State, and Color Variations

Before an edition is finalized, an artist and printer may produce trial proofs, state proofs, or color proofs. These early versions help them test out the image before committing to the final edition.

A trial proof might explore different color schemes, paper textures, or even slight design changes. A state proof could show the image at an earlier stage before final details were added. A color proof is just what it sounds like: a test of different ink combinations to see what works best.

These proofs are often unique. Unlike the finished edition, where all prints match the final chosen version, these earlier versions vary and may never be repeated.

Some artists, like Andy Warhol, turned trial proofs into part of their market strategy. Warhol’s proofs often featured alternate color palettes that weren’t used in the official run. Instead of discarding them, he sold them as standalone prints. Today, these alternate versions are considered rare and collectible, sometimes more so than the standard editions.

What is a B.A.T. and Why It’s Important

Once the artist is happy with the image and all the testing is complete, they approve a final version known as the B.A.T. This stands for bon à tirer, a French phrase meaning "ready to print." This proof becomes the standard for the rest of the edition.

The printer uses the B.A.T. as the benchmark. Every print in the edition is matched against it to ensure consistency. The B.A.T. itself is unique and is usually kept by the printer as part of the print’s history. It's not typically sold, though sometimes it may enter the market years later.

How to Confirm if a Print Is an Original

If you're looking to collect, you’ll want to know if the piece is a verified original print. This means the work must meet a few clear standards. First, the print must come from a limited edition that the artist directly created or approved. Second, it should match other known works from the same edition or appear in the artist’s official record, called a catalogue raisonné.

When a print is listed for sale, especially by a gallery or auction house, the details should be spelled out. You’ll want to see the artist’s name, the title, the print technique (like screenprint, etching, or lithograph), and the year it was made. The listing should also show whether it’s part of the regular edition or a proof.

In high-end listings, the catalogue raisonné number may also be provided. This cross-checks the print against a published list of the artist’s known works. If it appears in that record, it’s one more layer of proof that the print is authentic.

Why Paper Matters in Fine Art Prints

The Role of Paper in Printmaking

Paper is not just a surface that holds ink. It plays an active role in how a print looks, feels, and lasts over time. In fine art printmaking, the type of paper used can change everything. Texture, thickness, tone, and even how the ink settles into the surface all depend on the paper. That’s why serious collectors and print specialists pay close attention to it. Artists choose their paper on purpose. It’s not random. The final image depends just as much on the paper as it does on the plate, stone, or screen.

Why Collectors Care About Paper Type

A trained eye will always look at the paper first. When cataloguing a print, professionals always list the paper type because it gives insight into the print’s quality, age, and authenticity. Some papers are machine-made. Others are handmade with natural fibers like cotton, linen, or kozo. Handmade paper tends to be more durable and has a deeper texture, which can give the ink more depth. You might also see terms like wove paper, laid paper, or Japan paper. These tell you how the surface was made and how it reacts to ink.

Artists often work closely with printers to select paper that matches the tone they want. A rough-textured paper might soften harsh lines. A smooth one will keep everything sharp and clear. Some papers absorb ink deeply. Others let it sit on top. That changes how the colors look and how much detail you can see.

Watermarks and What They Mean

Watermarks are another thing collectors look for. These faint marks are built into the paper during its production. They can show a maker’s name, a date, or a symbol. Watermarks can help confirm where and when the paper was made. That matters when authenticating older prints or verifying a specific edition.

A watermark in the right place can also raise a print’s value. It shows the artist or printer cared about quality from the start. Our catalog entries always mention a watermark if it’s there. It’s one of many small signs that help buyers judge whether a piece is original, rare, or historically important.

Artists’ Choices: From Jasper Johns to Andy Warhol

Different artists have different views on paper. Jasper Johns is known for being very particular about it. He insisted on high-quality, heavyweight paper for many of his prints. He wanted a solid, tactile surface that would hold the ink well and make the image feel more sculptural.

On the flip side, Andy Warhol did the opposite. For his Soup Can prints in the 1960s, he picked thin, cheap paper on purpose. It wasn’t because he couldn’t afford better; it was a statement. Warhol wanted his art to feel like mass media. He wanted people to think of advertisements, newspapers, and everyday packaging. The paper wasn’t just a surface. It was part of the message.

These choices show how much paper matters. It’s not just about durability or luxury. It’s part of the concept. It changes how we read the work and how we understand what the artist wanted to say.

Full Sheet vs Trimmed Margins

Condition is another big deal when it comes to paper. One thing we always report is whether the print has full margins or if it has been trimmed. A full sheet means the paper hasn’t been cut or altered since it was printed. It’s exactly how it left the studio. That’s important for both value and authenticity.

Trimming can lower a print’s value, even if the image is untouched. It changes the proportions and removes part of the original artifact. Sometimes margins include important information like edition numbers, titles, or signatures. Even when they’re blank, full margins show the print is in its original form. Collectors usually prefer this.

Paper Is Part of the Art

To most people, paper might seem like a background detail. But in fine art prints, it’s central. It affects how the image looks, how the surface feels, how long the print lasts, and how it’s judged in the market. It also reflects the artist’s intentions. Whether they picked thick, textured paper to add weight and presence, or flimsy commercial stock to challenge the idea of "high art," the choice of paper says something. For collectors, paying attention to these choices is key to understanding and valuing prints the right way.

How Printmaking Studios Affect Price, Quality, and Collector Interest

Why the Studio Matters in Printmaking

Where a print is made plays a big role in its value, its quality, and even how collectors view it. Some printmaking studios are known worldwide for the level of detail and craftsmanship they bring to every edition. Others might be smaller, lesser known, or newer, but still carry strong reputations among collectors and curators. Either way, the studio behind the print can make a clear difference in how that work is received, both artistically and financially.

Catalog Information Tells You a Lot

When a print is officially catalogued or listed, the entry usually mentions the studio where it was made. This isn’t just a technical note. It gives collectors, dealers, and institutions insight into the background of the piece. Knowing where a print was produced can speak volumes about its printing technique, paper quality, edition control, and overall care in production.

Studios can vary in size and setup. Some are large, highly technical operations with advanced equipment and full production teams. Others are small workshops run by just a few people. But size doesn’t always equal quality. It’s more about the reputation, the skill of the master printers involved, and the studio’s history of collaboration with top artists.

Major Studios with Big Names Behind Them

There are a handful of standout print studios that consistently produce high-value, museum-grade prints. Collectors and experts tend to pay special attention to them, especially when it comes to Post-War and Contemporary art.

ULAE (Universal Limited Art Editions) in West Islip, Long Island, is one of the most respected names in American printmaking. Since the 1950s, ULAE has worked closely with some of the biggest artists of the 20th and 21st centuries. Their prints are known for precision and quality, and collectors often seek them out specifically.

Tyler Graphics, based in Mount Kisco, New York, has a legendary status in the print world. Founded by master printer Kenneth Tyler, the studio has helped push technical boundaries in printmaking. Tyler’s collaborations with major artists like Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, and Frank Stella resulted in prints that broke new ground. Because of this, the name "Tyler Graphics" on a print can carry real weight and increase its market value.

Gemini G.E.L. (Graphic Editions Limited) in Los Angeles is another major player. Since the late 1960s, they’ve worked with artists like David Hockney, Robert Rauschenberg, and Ellsworth Kelly. Gemini G.E.L. editions are recognized for bold experimentation, especially in print formats that combine sculpture, installation, or unusual materials. They’re often technically complex and can be expensive, but they also draw serious attention from high-level collectors.

Paragon Press in London is well-known for its partnerships with leading British and European artists. The studio is newer compared to some American giants, but its reputation for producing clean, consistent, high-quality work has made it a serious name in contemporary printmaking. Works printed at Paragon often end up in major galleries and collections.

These are just a few examples. New studios are emerging all the time. And some older, more obscure print shops are being rediscovered as interest in overlooked artists and movements grows.

Blindstamps and Studio Marks Matter

Some studios add what’s called a blindstamp to their prints. This is a small mark, usually embossed, sometimes inked or stamped, that’s pressed into the paper. You might find it near the margin or on the back of the sheet. Blindstamps are a way for studios to sign off on the work, kind of like a seal of authenticity from the place where the print was made.

For collectors, spotting a blindstamp can confirm the edition’s origin. It also helps establish trust in the print’s quality. In many cases, especially with prints from high-profile artists, the presence of a recognized studio’s blindstamp can affect the piece’s market value. It connects the print directly to a history of skilled production and controlled distribution.

Collectors Often Follow the Studio, Not Just the Artist

Many serious collectors don’t just follow artists. They follow studios, too. Some build entire collections based around the output of a single printmaking workshop. This kind of collecting focuses on the craft of printing just as much as the creativity of the artist.

Studios like Tyler Graphics and Gemini G.E.L. have such strong reputations that even lesser-known artists who worked with them can get attention. That studio association becomes a kind of quality guarantee.

Knowing the studio behind a print lets you see the bigger picture. It adds context to the work. It helps you understand the techniques used, the materials chosen, and the overall approach to the edition. And most importantly, it gives you more tools to evaluate value, rarity, and long-term potential.

Do All Fine Art Prints Have Signatures? What It Means If Yours Doesn't

One of the most common questions people ask when looking at prints is whether every print should be signed. The short answer is no, not all prints are signed by hand. And just because a print doesn’t have a signature in pencil or ink doesn’t mean it’s not authentic or valuable.

At auction houses and trusted galleries, most of the prints you'll see are signed, usually by the artist. But that doesn't apply to every edition ever made. Some artists had different practices, and the way they chose to sign or not sign their prints can vary by period, printer, and project.

Take Andy Warhol, for example. Many of his prints were not signed by hand. Instead, some were stamped with a signature, either during his lifetime or after, by someone managing his estate. These stamp-signatures were often applied by The Estate of Andy Warhol or The Andy Warhol Foundation, using rubber stamps or embossed marks. This was especially common in portfolio sets or editions that were finished after his death. Still, these works are considered legitimate Warhol prints and are widely collected.

Pablo Picasso followed a similar practice. Though he did hand-sign many of his prints in pencil, he also produced a number of editions that were signed with a facsimile signature - a mechanical reproduction of his signature added during the printing process. In other cases, the only signature appears on the cover sheet of a portfolio rather than on each individual print. When buying or collecting Picasso prints, this context is important. Not all unsigned works are after-market reproductions. Some are exactly how they were issued.

Another thing to understand is that artists don't always write their full name. Some use initials. This isn't unusual and doesn't hurt the value if it's consistent with the artist’s known habits. For example, Lucian Freud and Richard Diebenkorn often signed with just their initials. They did it deliberately, and collectors recognize these marks as authentic.

Sometimes, especially in collaborative or workshop settings, an artist may choose not to sign each print. The print might still be part of a limited edition, numbered and printed under the artist’s supervision, but without a personal signature. These editions are still considered original prints (not copies or posters) and are still part of the artist’s body of work.

There are also practical reasons why a print might not be signed. In the case of very large editions or late-career projects, some artists approved the work but didn’t sign every single print. And in other cases, especially with posthumous editions or estate-approved prints, the work might carry a stamped signature or a certificate of authenticity instead.

If you're looking at a print that seems unsigned, the first thing to check is whether it’s part of a known edition. See if there’s an edition number, a workshop stamp, a publisher’s mark, or some kind of catalog reference. These things matter just as much as a signature when it comes to verifying a print’s legitimacy.

Also, look at where the print came from. If it was sold by a known gallery, auction house, or directly through a trusted estate, an absent signature isn’t necessarily a red flag. In fact, some of the most sought-after prints in the market have no signature at all.

What truly matters is the combination of details: the artist’s intent, the edition size, the print technique, the provenance, and how the print was issued. A missing signature doesn’t always mean something is wrong. But it does mean you should do a little homework and understand what’s typical for that specific artist and edition.

So, don’t dismiss a print just because there’s no signature in the corner. If the work is part of a verified edition and it aligns with how the artist normally released prints, it could still be an authentic, valuable, and highly collectible piece.

Which Artists Should You Watch at Auction?

If you’re interested in collecting fine art prints, the first step is to know which artists have shaped the field and which ones continue to influence it. Printmaking has a long, layered history, and some of the biggest names in art used it to push boundaries and try out new ideas. These artists didn’t just use printmaking as a side project. They treated it as a serious part of their work and helped move the whole medium forward. That’s why their prints still hold strong at auction today.

The Legacy of Albrecht Dürer

Start with Albrecht Dürer. He was one of the first true masters of printmaking. In the late 1400s and early 1500s, he raised the bar with his woodcuts and engravings. Dürer didn’t just reproduce images. He turned printmaking into a fine art. His prints showed detail and precision that hadn’t been seen before. Works like The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and Melencolia I became models for how powerful a black and white image could be. Dürer helped prove that prints could hold the same cultural and commercial weight as paintings.

Rembrandt’s Printmaking Revolution

Next came Rembrandt in the 17th century. He took etching to a whole new level. He wasn’t afraid to experiment. He worked directly on copper plates like he was sketching in a notebook. His lines were loose, expressive, and full of depth. He also played with light and shadow in a way that gave his prints real emotional impact. Many of his self-portraits and biblical scenes are still studied today for their technique and intensity. Rembrandt helped redefine what etching could do. At auction, his original prints still draw major interest from collectors.

Toulouse-Lautrec and the Birth of Modern Posters

In the 19th century, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec made a name for himself in Paris with bold, colorful lithographs. He focused on nightlife, cabarets, and performers, especially at the Moulin Rouge. His posters weren’t just advertisements. They were pieces of art that captured the energy of the time. Lautrec used flat colors, strong outlines, and striking compositions to grab attention. His style shaped visual culture in a lasting way, and his original prints remain valuable and highly collectible.

Picasso and the Art of Reinvention

Pablo Picasso took printmaking and turned it into a lab for invention. He didn’t just stick with one method. He tried them all: etching, lithography, linocut, and more. Over his long career, he constantly played with new ways to create texture, shape, and contrast. He often worked closely with master printers to push technical boundaries. His series of bullfight scenes, faces, and mythological images in print form are as influential as his paintings. Because Picasso worked in many styles and methods, his prints offer a wide range of entry points for collectors. At auction, they vary from highly accessible to extremely rare and high value.

Warhol’s Impact on Contemporary Print Culture

In the 20th century, Andy Warhol made screenprinting one of the most important tools in modern art. His bold, repetitive images of Marilyn Monroe, Elvis, soup cans, and dollar bills turned mass production into a creative act. Warhol worked with professional printmakers, but he was hands-on. He chose colors, ink textures, and paper types. He also wasn’t afraid to experiment with flaws. Sometimes misregistrations and ink smudges were part of the final look. His prints made the process itself visible and central to the art. Today, Warhol prints are staples in major auctions and tend to attract aggressive bidding, especially when they’re rare variants or signed editions.

Jasper Johns and the Printmaker’s Mindset

Jasper Johns is another major figure in the history of contemporary printmaking. From the 1960s through to today, he has used prints to rework ideas and challenge visual habits. Flags, numbers, and targets show up often in his work, but he changes their meaning through layering and repetition. He has also used lithography, screenprint, intaglio, and even handmade paper to create prints that feel as rich as paintings. Even in his 80s, Johns continues to produce new work, and his prints remain strong performers in both primary and secondary markets.

Printmaking as a Timeline of Innovation

The history of printmaking is also a record of change. From hand-carved woodblocks in the 15th century to copperplate etching, then onto lithography, screenprinting, and finally digital printing today, the medium has always evolved with the times. Artists use it not just to reproduce ideas, but to explore new ways of thinking and seeing.

Each transformation in printing technology opened new paths for expression. And each major printmaker - Dürer, Rembrandt, Toulouse-Lautrec, Picasso, Warhol, Johns - used those tools to stretch the limits of what prints could do.

So when you're watching auctions or thinking about building a collection, look for prints that connect with this history. Focus on artists who didn’t just use printmaking as a side note but made it part of their core practice. Those are the works that stand the test of time, both in museums and in the market.

Why Prints Matter in a Broader Art Collection

Prints hold real weight in a serious collection. They aren’t just filler or extras. They offer depth, variety, and context. Whether you’re collecting for personal enjoyment or long-term value, prints help build a richer and more complete picture of an artist’s full creative output.

Some collectors focus only on prints. Others fold them into larger collections of painting, drawing, or sculpture. Either way, prints offer something unique. They often imitate the same ideas, forms, or subjects that appear in an artist’s other work. In many cases, you’ll find similar figures, colors, or compositions repeated across different media. That connection makes prints useful for understanding how an artist’s style develops and changes over time.

Take Picasso, for example. His prints track right alongside his paintings and sculptures. They reflect the same phases, the same obsessions, the same experiments. His approach to printmaking changed over the years, just like his painting style did. You can see him test out visual ideas on paper, working through them in a looser or more playful way than he might on canvas. The same goes for Jasper Johns. His prints explore motifs like flags, numbers, and targets, just as his paintings do. But when you look at the prints closely, you also see how his technical skills evolved. You see how he pushed the limits of each printmaking method, trying out new textures, materials, and methods.

Prints don’t just show what an artist made. They show how they thought, how they experimented, and how they grew. That kind of insight is hard to get from just one sculpture or one painting. So adding prints into the mix helps round out a collection. It builds context. It gives you a fuller view of the artist’s work as a whole.

But it’s not just about history or depth. Prints also make collecting more accessible. A print gives you a direct connection to an artist’s hand, without the six or seven-figure price tag that often comes with a painting or bronze. Many prints are original works, not copies or reproductions. They were made as part of the artist’s studio process, often under the artist’s close supervision or even hand-signed and numbered. So when you buy a print, you're still buying something real and deliberate.

For new collectors, this is where prints can be a great entry point. You can explore big-name artists and iconic styles without the barrier of high costs. A print lets you start small, take your time, and still collect pieces that matter. You get the chance to learn about the artists, the printmaking techniques, the paper types, the edition sizes, and all of that knowledge builds up over time. Starting with prints helps you train your eye. You develop your own sense of what you like and why.

Even experienced collectors often return to prints because of their range. You can collect across styles, across movements, across decades. You can compare early and late works, rare editions, or prints that were never published. The options are broad, and the insights are valuable. Prints don’t just support a collection. They can shape one, refine it, or take it in a new direction altogether.

How to Care for Art Prints the Right Way

Framing Comes First

The way you frame your print is the most important choice you’ll make when it comes to preserving it. That single step will protect the work for years to come. It’s not just about looks. The right frame, with the right materials, acts like a shield. It guards against sunlight, moisture, dust, and handling damage.

You need to work with a framer who knows how to handle fine art prints. This isn’t something you want to do on the cheap with off-the-shelf materials. A good framer will use acid-free backing, UV-filtering glass or acrylic, and proper hinging methods that don’t damage the paper. Archival framing isn’t always expensive, but it does require care and skill. Don’t assume a standard frame from a department store will do the job. It won’t.

Ask the framer if they’ve worked with fine prints before. They should understand that the paper, margins, and ink all need to be protected without being altered or cut. No adhesive should touch the artwork itself, and the print should never be glued down or pressed flat against the glazing.

Why You Should Never Trim a Print

One common mistake people make is cutting the paper edges to fit a smaller frame. Don’t do that. The full sheet is part of the artwork, even if it seems like just blank paper. Cropping or trimming a print destroys its value and changes its integrity. In some cases, those edges include watermarks, signatures, edition numbers, or other marks that prove authenticity.

Collectors and dealers expect to see a full, untrimmed sheet. Once it's cut, the print is no longer in its original condition, and that affects both resale value and historical importance.

If your print doesn’t fit a ready-made frame, get a custom one made. It’s worth the investment.

Sunlight Damages Prints Over Time

Prints with bold, bright colors are especially sensitive to light. Direct sunlight will fade pigments, sometimes permanently. Even black and white prints can turn yellow or develop uneven fading when left in strong natural light for too long. That’s why UV-filtering glass or acrylic is standard in museum-quality framing. But even then, don’t hang the print in direct sunlight.

Choose a place with soft, stable lighting. Artificial light is usually safer, but avoid harsh spotlights. Heat and brightness speed up fading and break down paper fibers.

Humidity Is a Hidden Threat

Moisture is another major problem. It warps paper, causes foxing (those brown mold-like spots), and can even make ink run or lift. Bathrooms, kitchens, and basements are risky spots for hanging prints. Don’t mount them near radiators, vents, or windows where condensation might collect.

The best environment is dry, cool, and stable. If your area gets humid, a dehumidifier can help. If your home tends to be dry in the winter and damp in the summer, aim for consistency. Fluctuating humidity levels are just as bad as high ones.

Handle With Clean, Dry Hands

Even if you’re just moving the print for a short time, don’t touch the paper directly with your bare hands. Oils and dirt from your skin can leave stains that build up over time. If you must handle the print, use clean cotton gloves or only touch the edges of the frame or backing.

If the print is unframed, don’t rest it directly on rough surfaces. Put down a clean, smooth barrier, like acid-free tissue paper, so the ink or paper doesn’t get scratched.

Framing Isn’t a One-Time Thing

Once a print is framed, check on it now and then. Look at the corners. Is the paper starting to buckle? Are there any signs of mold or moisture? Has the color faded? These are signs you may need to reframe the print or move it to a better spot.

If you notice condensation inside the glass, remove the frame and let the print dry in a safe, clean place before the moisture causes real damage. Then reframe it with better sealing and better placement in your home.

Talk to an Expert If You’re Not Sure

There’s no shame in asking for help. If you're not sure how to frame or care for your print, talk to someone who works with prints often. It’s better to ask upfront than to ruin a piece by guessing. A quick consult can save you time and money in the long run.

High-End Prints and Multiples: What the Market Is Paying For

The print market has always been a space where collectors can find major works by important artists at a fraction of painting prices. But that doesn't mean they're cheap. Some prints, especially rare editions or those with complex techniques, can sell for tens of thousands of dollars. Below are real examples of high-value prints that give a sense of what collectors are looking for and what makes these works command such high prices.

George Condo’s Etching and Drypoint

George Condo’s Laughing Clown Composition, made in 2020, is a perfect example of how contemporary printmaking can push value. Created using etching and drypoint on Hahnemühle paper, it measures just under 20 by 24 inches, with a larger sheet size. This piece was estimated between $20,000 and $30,000. Condo’s work often blends humor with discomfort, and collectors respond to the tension in his lines. The use of drypoint, which produces sharp, dark marks, adds to the visual punch. Combine that with his strong collector base, and it’s easy to see why this print sits in a high range.

Robert Rauschenberg’s Monumental Lithograph

Rauschenberg’s Kitty Hawk from 1974 is a lithograph printed on brown Kraft wrapping paper, an unusual material that adds texture and depth. At nearly 79 inches wide, the scale alone makes this work striking. It carries an estimate of $12,000 to $18,000. Rauschenberg was known for breaking rules in both form and material, and this print reflects that risk-taking approach. Even decades later, his prints still appeal to collectors who want work that feels both historic and experimental.

M.C. Escher’s Collectible Woodcuts

Escher's prints are among the most recognized in the world. His 1946 woodcut Horseman was printed in color on laid Japan paper. Though smaller in size, its rich color and precise craftsmanship push it into the $10,000 to $15,000 range. A separate work, Metamorphosis III, made between 1967 and 1968, is even rarer and commands a higher estimate between $25,000 and $35,000. Both works show his obsessive attention to detail and his deep knowledge of geometry and spatial illusion, which remain highly desirable traits in printmaking today.

Roy Lichtenstein’s Bold Pop Style

Lichtenstein’s Blonde from his 1978 Surrealist Series uses bright lithographic colors printed on Arches paper. Measuring over 21 inches tall, this print captures his signature comic-book style and pop iconography. It's estimated between $25,000 and $35,000. Lichtenstein's prints are always in demand, especially ones that feature strong visuals and are part of limited, dated editions. His use of bold lines and flat color keeps the work accessible but striking, which helps drive up value in both galleries and auctions.

Louise Bourgeois and the Hand-Colored Touch

The Ainu Tree by Louise Bourgeois combines lithography with hand coloring in red crayon. That added personal touch matters a lot in the print market. Even though this work is more modest in price, with an estimate of $4,000 to $6,000, it stands out. Collectors often seek prints where the artist added something by hand, which makes each piece feel closer to a one-off. Bourgeois is already a major name, and pieces like this only increase in value over time.

Glenn Ligon’s Text-Based Etchings

Ligon’s Untitled (Four Etchings), made in 1992, is a complete set of four text-based works. Each one uses aquatint, which creates a deep, velvety texture, on Rives BFK paper. This set carries a strong estimate between $30,000 and $50,000. His use of language as visual form, paired with bold statements on identity and race, gives the work both visual and political weight. Sets like this are rare, and serious collectors often jump on full portfolios when they come to market.

Vija Celmins and Photoreal Lithographs

Celmins’s Untitled Portfolio from 1975 includes four lithographs printed on handmade rag paper. Each one features her signature style: soft, almost photographic renderings of natural surfaces like ocean waves or starry skies. With an estimate of $60,000 to $80,000, this set is among the most expensive on the list. Her reputation for obsessive detail and technical control makes her prints highly collectible, and her editions are small and carefully produced, which adds to the demand.

Eric Fischl’s Narrative Printwork

Fischl’s Year of the Drowned Dog, created in 1983, is printed on six large sheets using aquatint and drypoint. Combined, the work spans over 70 inches in width. Its narrative structure, painterly feel, and layered technique help support its $15,000 to $20,000 estimate. Fischl's work explores emotional depth, memory, and conflict, and his prints carry the same weight as his paintings. Larger formats also tend to perform better in terms of auction value.

Wayne Thiebaud’s Bright Etching

Thiebaud’s Daffodil from 1979 is a classic example of his use of bright, edible color. Printed with etching and aquatint on Somerset paper, this work reflects his best-known themes. The estimate ranges from $18,000 to $25,000. Collectors love Thiebaud's clean forms, nostalgic tone, and painterly textures, which all come through clearly in his prints. The use of color and shadow in this etching shows how printmaking can match the depth of oil painting.

Ed Ruscha’s Conceptual Lithographs

Archi-Props, a full set of eight lithographs made between 1993 and 1997, showcases Ruscha’s dry, conceptual humor. The works are small in size but powerful in tone. They’re printed on Rives BFK paper, with the largest image under 10 inches wide. The set’s estimate is between $25,000 and $35,000. Ruscha’s prints often look simple but carry sharp meaning. Complete sets, especially those spanning several years, are always more attractive to serious collectors.

Andy Warhol’s Rare Artist Book

Wild Raspberries, made in 1959, is a rare book of offset lithographs by Andy Warhol. Sixteen of the prints are hand-colored with watercolor. This early work is playful and light, but also shows the foundations of Warhol’s later style. At an estimated $40,000 to $60,000, it proves that artist books and prints can reach just as high as larger works, especially when tied to a name as iconic as Warhol. The handmade feel and vintage charm add to the appeal.

Nancy Graves and Large-Scale Printmaking

Nancy Graves’s Stuck, The Flies Buzzed is a huge print, both in technique and size. At over 90 inches tall, this etching combines aquatint, drypoint, screen printing, and collage. Despite the monumental scale and mix of methods, it holds a relatively modest estimate of $4,000 to $6,000. This makes it a potential value opportunity for collectors who want ambitious work without breaking the bank. Graves’s work blends structure with chaos, and this print shows how mixed techniques can create a dense, textured surface that feels sculptural.

In the End

What all these examples show is that printmaking is a serious space for collectors. The materials, the process, the edition size, and the artist’s reputation all shape the final value. While some prints come in at a few thousand dollars, others reach well past $50,000. When a print includes hand coloring, uses complex methods like aquatint or drypoint, or comes from a complete portfolio, the price usually climbs. And when it comes from an artist with museum-level recognition, collectors take notice fast.