Introducing Kirikane: A Timeless Japanese Gold-Leaf Art

Kirikane is an ancient art form from Kyoto. It brings gold leaf to life on Buddhist statues and paintings. And it speaks to the deep beauty of Buddhism through richly detailed patterns. This method uses ultra-thin strips of gold, silver, or platinum leaf. Artists cut them with precision and then glue them in place with fine brushes. The effect is delicate. The result is stunning.

Origins of Kirikane Art in Japan

This craft came to Japan in the mid-7th century. It arrived alongside Buddhist art from Korea and China. The oldest example still in Japan lives at Hōryū‑ji Temple’s Tamamushi Shrine. It proves how long this technique has shaped sacred imagery. Kirikane is not an imitation. It is uniquely Japanese. And it remains alive today.

Kirikane’s Rise and Decline

Kirikane thrived from the Heian through Kamakura periods. Buddhism was on the rise. And this art reflected that spiritual surge. But as centuries passed, the Muromachi and Edo eras saw a change. Gold paste replaced gold leaf, and Buddhist art fell out of favor. Kirikane nearly vanished. Only a few artisans kept it alive in major temples like Higashi Honganji and Nishi Hongwanji.

Modern Revival and Cultural Preservation

Recently, interest in Kirikane has surged again. Now it is valued both as Buddhist art and fine craft. Three artisans have even earned the title of Important Intangible Cultural Heritage Holders, or Living National Treasures. This recognition speaks to the skill and cultural value of the technique.

The Materials Behind Kirikane

A single sheet of gold leaf used in Kirikane is incredibly thin - just 10 micrometers. A soft breath can blow it away. Artisans cut it with a bamboo sword about 20 millimeters thick, after drying it for five to ten years. Cutting by eye, they sometimes trim the leaf even thinner than a strand of hair.

Applying Kirikane: Technique and Detail

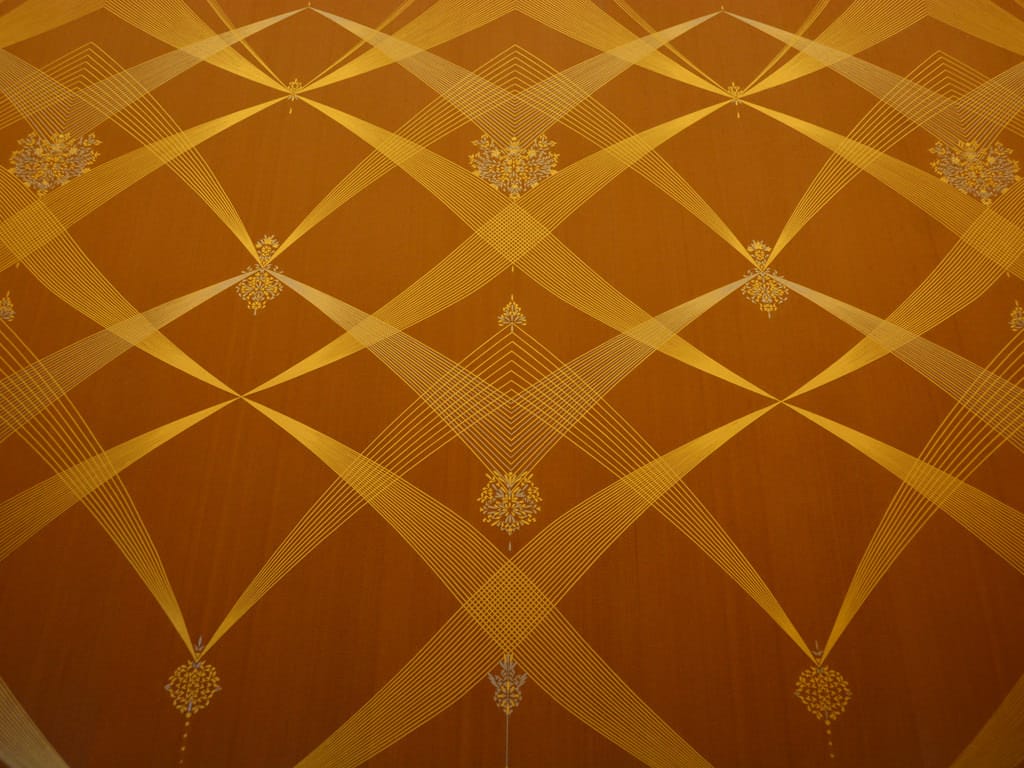

Once cut, the thin strips are layered. Brushes and glue are used to place each piece with care. The patterns often mirror nature: leaves, animals, light, and ordinary things. And they draw from classic Japanese designs. The result changes with light and angle. Every view gives a new visual rhythm.

Kirikane’s Icons: The Keepers of Tradition

Only three people have earned the status of Important Intangible Cultural Heritage Holders in Kirikane. One of them was Nishide Daizō from Ishikawa Prefecture. Born in 1913, he became a holder in 1985. He learned the art while restoring Buddhist pieces. Then he made it his own. He used it to decorate wood vessels shaped like animals, covered in vivid gold lines and floral designs. His works are now held in museums. Kirikane itself gained heritage status back in 1981.

The Complete Tale of Kirikane

Kirikane is more than decoration. It blends art, history, and devotion. It spans continents and generations. And it survives through craft and culture. From temple treasures to museum galleries, this fine art carries tradition forward. It shows what care, patience, and skill can create. And it reminds us of the lasting power of beauty.

With that said, let's move on to the full, complete story of this wondrous craft:

History & International Presence of Metal Leaf in Glass

Outside Asia, similar techniques emerged in Hellenistic Mediterranean glassware between 300 BCE and 30 BCE. Makers sandwiched gold-leaf plant motifs between two layers of clear glass. These artifacts include gold-leaf glass bowls, plates, cups, and scatula. By the 4th century CE, gold-leaf glass medallions, bases, and inscribed panels appeared. These items show patterns carved into the leaf under glass; examples of kirimon motifs. The technique traveled further. By the 9th and 10th centuries, Abbasid-era Iraq and Syria had gold-leaf glass bowls, cups, and tiles. Early 12th-century Zangid Syria produced gold-leaf glass bottles. All suggest a global exchange of metal leaf craft.

Early Metal Leaf Use in Northern Wei China

In China’s Northern Qi era (550-577 CE), two bodhisattva statues feature kirikane. Gold leaf decorates chest ornaments and arm bracelets. On one statue, a red skirt is sectioned in green and red squares, each with white round motifs bordered by kirikane. Another statue worn belt-like bands adorned with double hexagons enclosing turtles, and the skirt hem shows vertical hexagons filled with three-leaf plant designs.

Asuka and Hakuhō Period Origins in Korea and Japan

In early 6th-century Korea, in Baekje, excavations in the tomb of King Muryeong’s queen in Chungcheongnam-do revealed a wooden headrest. That object bore a tortoise-shell design in gold-leaf strips on red lacquer. It shows the use of metal leaf before adoption in Japan.

In mid-7th-century Japan, kirikane came with Buddhist sculpture and paintings from Korea and China. Hōryū‑ji Temple’s Tamamushi Shrine shows the oldest surviving kirikane in Japan - small long diamonds on the shrine’s base. A more advanced example resides in Hōryū‑ji’s Kondo, where the Four Heavenly Kings have diamond-shaped kirihaku on the Broad‑Vision King, round foils and four‑leaf motifs on the Many‑Armed King. These items indicate that Japanese artisans at the time crafted metal leaf and mastered cutting and patterning.

Kirikane in Hakuhō Buddhist Painting

In Hakuhō culture, the Takamatsuzuka Tomb mural presents celestial sun and moon imagery on the ceiling using gold and silver leaf foils - silver now tarnished gray. Star constellations were made with gold-leaf dots roughly 0.9 cm in diameter.

Nara Era Use in Temple Sculpture and Imperial Treasures

During the Nara period, kirikane decorated repainted lacquer Four Heavenly Kings at Tōdai‑ji’s Hokkedō Hall. It also appears on garments and armor of the clay Four Heavenly Kings in the Kaidan-dō Hall. The Shōsō-in storehouse holds treasures featuring kirikane on a Silla zither and a phoenix-shaped metal ornament. You can also see diamond, pine-needle, flower, and flowing lines on the pieces. The human-shaped remains from Shōsō‑in are decorated with flower and leaf patterns in kirimon motifs.

Heian Period Kirikane

In the Heian period, kirikane appeared in works made in the ninth century,like the Shitenno statues at Toji Temple. The Jikokuten statue uses straight-line patterns and dotted designs. It doesn’t include curved motifs. That style carries on from the Nara period. Curved kirikane patterns only show up later, in the early tenth century. That marks a change in Buddhist art, from Tang style to Japanese style.

Around the eleventh century, kirikane first appears in Buddhist paintings. One key example is the Nine Rafts of Rebirth panels on the doors of Phoenix Hall at Byodoin Temple. That counts as the earliest such appearance in religious art. In late Heian, artists used fine kirikane patterns in pieces like the Nirvana painting at Kongobuji Temple on Mt. Koya and the Golden Coffin Emergence painting held by Tokyo National Museum. These works prove how richly kirikane grew as Buddhist art flourished.

Archaeologists also found glass jars beneath the pedestal of the main Amida Buddha at Byodoin. Among about 84 fragments, three had kirikane decoration. This was the first time scholars found gold-leaf detail on ancient glass in East Asia.

Kamakura and Nanbokucho Period Style

In the Kamakura period, around the late twelfth to fourteenth centuries, artists painted the flesh of Buddhist statues with gold pigment. They used kirikane over a base coat of gold or yellow earth pigment on the robes. This method became known as full-gilding. New patterns emerged then: lotus scrolls, swastika chains, thunderbolt patterns linked together, spider web motifs, and little birds. These designs came from the style changes influenced by Southern Song China.

Through the Muromachi and into Edo period, kirikane gradually became more formal stylized. Gold pigment replaced gold leaf in many designs. That meant fewer artists mastered the old method. In later years, the skill survived only under the protection of the two Honganji temples in Kyoto. It was limited to a few practitioners.

In modern times, people started working to bring back kirikane. Lectures and workshops now teach the method again. The craft is slowly gaining recognition outside official temple circles.

Kirikane in Ancient and Global Context

Although this focused on Japanese kirikane, gold leaf in glass plates and medallions dates back much further. We see examples from ancient cultures like those held at Reggio di Calabria Archaeological Museum from the third century BCE, and in Hellenistic works in the Metropolitan Museum. These include goblets with gold-leaf letters and medallions with portraits dating from the third to fourth century CE.

There are even gold-leaf glass mosaic tiles from the ninth to twelfth-century Syria in collections at the Metropolitan and British Museums.

In East Asia, the sixth-century headrest of Queen Dishu from Baekje shows hexagonal kirikane patterns with phoenixes, fish dragons, flying deities, and lotus in color.

And in China’s Northern Song dynasty, there’s an eleven-faced Kannon statue using kirikane.

During Japan’s Kamakura era, sculptors like Kaikei created kirikane Buddha statues. The early thirteenth-century Fudo Myoo statue in the Metropolitan Museum shows this. The thirteenth-century Jizo statues there also carry kirikane. Fourteenth-century Fudo Myoo statues preserve these patterns on the front and back. And on into Edo, there are Kannon and Seishi statues from the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries reflecting that tradition, found at the same museum.

Tools and Techniques

This section explains the tools and methods needed for kirikane. It covers the types of leaf used, how they are prepared, and the equipment needed to cut and bond them.

Types of Metal Leaf

The main materials are gold, silver, and platinum leaf. Each type behaves differently and requires specific techniques.

Beveled Gold Leaf

Beveled or “edged” gold leaf shows grid patterns from traditional pounding techniques. This type is popular because it is softer and easier to handle, making it ideal for intricate layering and cutting.

Standard Gold Leaf

Gold leaf is beaten until it’s only one ten‑thousandth of a millimeter thick, with each sheet about 11 square centimeters. For straight patterns, artists stack six layers. For curves, they use five. There are two main kinds. Edged gold leaf comes from Japanese papermaking. And block‑cut gold leaf is pasted between glassine sheets. But that type is stiffer and harder to use. So, most artists choose edged gold leaf.

Because moisture affects bonding, stacking the layers is best done on dry sunny days. Avoid rainy or humid times like the monsoon.

Silver Leaf

Silver leaf was common in the Heian and Kamakura eras. But it tarnishes and turns dark over time. So modern artists rarely use it.

Buddhist Artist Leaf

This is a hybrid: a layer of silver leaf sandwiched between two layers of gold. It adds subtle depth and contrast in patterns.

Platinum Leaf

Today some artists use platinum leaf to mimic silver’s shine without the tarnish. It takes higher heat and more time to bond than gold.

Bonding and Cutting Tools

Several tools are essential for stacking and cutting the leaf.

Bamboo Tongs

These are used to pick up leaf sheets and position them for bonding. Bamboo does not create static, so the delicate leaf doesn’t stick to the tongs.

Iron Press

Modern methods use an iron instead of charcoal. You need a commercial iron without steam or temperature control. A household iron won’t get hot enough and may fail to bond properly, causing layers to peel over time.

When using the iron, lift it straight up and down to avoid wrinkles or tears. Bonding is complete when light smoke appears and the paper backing turns brown.

Some artists note that iron‑bonded leaf becomes stiff, making it harder to cut smooth curves.

Paper Backing

When using an iron, you need paper to prevent the leaf from sticking. The glassine sheets that come with leaf packages work fine.

Binchotan Charcoal

The traditional method uses dense lump charcoal made from ubame oak. It holds heat steadily and works well for leaf bonding.

Ash

Charcoal pieces are buried in ash in a hibachi brazier. The ash insulates heat and keeps the fire going. It must be sifted first; any debris can snag the leaf.

Hibachi Brazier

This is used to hold charcoal and ash, creating a stable hot zone for bonding.

Cutting the Leaf

Cutting tools include a cutting board, bamboo sword, small knife, and talc powder.

Cutting Board

A wooden board covered with deer hide. This provides a soft surface for cutting the leaf using a bamboo sword.

Talc Powder

Used to clean oils off the cutting board and tools so the leaf doesn’t stick.

Bamboo Sword

This tool is made from a split bamboo stalk sharpened along its skin to cut leaf with precision. It must be stored carefully, wrapped in cloth to prevent damage. The hard outer skin forms the cutting edge. If nicked, the sword won’t cut cleanly.

Small Knife

A carving knife is used to shape and sharpen the bamboo sword. It needs a sharp edge. Proper sharpening skill is essential.

Applying Leaf and Adhesive

Once cut, the leaf strips are applied to the surface using adhesives and fine brushes. Artists work slowly to lay each strip with precision. The glue must hold it firmly, yet allow some flexibility as light and angle change the design’s effect. This work requires steady hands and patience.

Tools, Materials, and Methods for Kirikane

This section explains the final group of tools and adhesives used in kirikane. It covers brushes, glue, and decorative motifs.

Brushes for Handling and Applying Leaf

From left to right in the toolkit are animal glue, seaweed paste, gold-leaf brush, and pick-up brush. The pick-up brush is used to lift thin gold leaf strips. And it’s better if it’s long and fine rather than thick and short.

The gold-leaf brush is used to apply seaweed paste to the target surface. It also guides where the gold leaf will go. The bristles can be made from any animal hair. But soft, absorbent bristles work best.

Yukihira Pot

A yukihira pot is a simple metal pot used to heat glue and seaweed paste together so they mix evenly.

Seaweed Paste (Funori)

Funori is an adhesive made from dried red seaweed. It softens when heated in the yukihira pot. Funori alone does not stick well. So it’s mixed with animal glue, with more funori than glue.

Animal Glue (Nikara)

Animal glue comes from boiled animal hides or bones. It dissolves in hot water. The common types are nikawa (hide glue), shichihonbon glue, deer glue (now made from cow), rabbit-skin glue, and fish glue. In kirikane, shichihonbon or deer glue is used most often.

To use, soak 10-15 g of glue in 200 cc water until soft. Then heat it in a warm water bath or over medium electric heat. Keep it between 50 to 70 °C, without boiling. Stir often to prevent burning. Strain the liquid through gauze when it’s done. It lasts 4 to 5 days in the refrigerator. Do not use it if it smells bad or loses stickiness.

Decorative Patterns

Kirikane often features repeated geometric patterns. Artists draw inspiration from nature, plants, animals, and everyday items. They might use a basic motif and change it up. Or combine shapes for variety. There is no strict rule on the designs. It's all about rhythm and repetition.

Natural Themes

This section shows patterns inspired by nature. Each design adds meaning and visual flow.

Arare

Arare uses square or diamond-shaped leaf pieces. Sometimes single, sometimes grouped in fours. They are scattered like hail across the surface.

Unryū

Unryū mimics drifting clouds. Artists use thin lines to outline soft cloud shapes.

Seigaiha

Seigaiha features overlapping arcs from concentric circles. It creates wave-like fans moving outward.

Tachiwaku

This pattern represents rising steam or vapor. It uses repeating bulging and narrowing curves. Artists often add small diamond or circle pieces between the curves.

Nami

Nami is a rhythmic wave design. Multiple lines flow together, either horizontally or vertically, to mimic water’s movement.

Hiashi

Hiashi shows sun rays. Thin, long, isosceles triangles are arranged with their points facing inward, forming a circular burst.

Maru-Kiri

Maru-kiri is a tool for punching out round leaf pieces. This lets artisans create smooth circular accents.

Hoshi

Hoshi means star. This design was introduced in modern times using punched round shapes. In earlier eras like Heian and Kamakura, they tried to mimic circles, but edges were never perfectly round.

Raimon

Raimon designs mimick lightning. They use straight lines folded repeatedly, creating zigzag patterns with spirals or peaks.

Plant Themes

This section covers motifs drawn from flora. Each pattern reflects a plant’s form or structure.

Asa no Ha

Asa no Ha resembles a hemp leaf. Inside a regular hexagon are six triangles. Lines connect the center of each triangle to three of its corners, making a star-like shape.

Karakusa

Karakusa shows twisting vines. Curved stems intertwine with small diamond leaf pieces, tracing loops and curls.

Kusa-bana

Kusa-bana means grasses and flowers. This pattern uses fine leaf strips to draw petals, leaves, and veins.

Dan-ka

Dan-ka is a layered floral motif. It uses cut leaf pieces (squares, diamonds, circles) clustered together to form stylized blossoms.

Hishi

Hishi mimics plant leaves. You can make it with two parallel diagonal lines or thicker diagonal cuts. Variants include nested diamonds and crossed diamond patterns.

Hōsōge

Hōsōge is a classic floral arabesque. It stylizes plants into decorative, symmetric flower forms.

Hishi - Diamond-Scale Pattern

The hishi motif mimics fish scales. It uses triangular gold leaf pieces. Those triangles interlock so their bases align. The result is a repeating diamond design filled with a fish-scale vibe.

Kikkō - Tortoise Shell Pattern

Kikkō resembles a turtle’s shell. It’s made from connected regular hexagons. The look is structured and geometric, like the shell of a tortoise. Some variations show up in samurai armor, where three hexagons form a Bīshamon Kikkō. Others nest within each other as “hole-within-hexagon” designs.

Hōō - Phoenix Motif

The hōō draws from the Chinese legendary phoenix. It stylizes the bird into a repeated pattern. The curves and feathers reflect something regal and mystical.

Animal-Themed Motifs

Kirikane often uses animals as its theme. The scale and tortoise patterns are one part. But you also find full-on stylized creatures carved into the art.

Net Pattern - Ami-me

Ami-me copies a fishing net’s mesh. It’s a simple grid that suggests woven lines, resembling everyday tools used in fishing.

Ichimatsu / Ishidatami - Checkerboard

Ichimatsu uses square gold leaf tiles. Each piece is the same size. They alternate in a checkerboard layout across the surface.

Kagome - Woven Basket Mesh

Kagome features interlinked hexagons with triangles on each side. It comes from bamboo baskets. The look is crisp. It’s an elegant, repeating mesh.

Kōshi - Lattice Grid

Kōshi is a basic grid of vertical and horizontal lines. Variations include changing the number or thickness of lines. At times, they run diagonally to form a slanted lattice.

Sangi - Abacus-Inspired Pattern

Sangi takes its cues from the sticks used in traditional Japanese math tools. Lines overlap like abacus rods. They create a linear, rhythmic pattern.

Shippō - Seven Treasures Rings

Shippō uses circles that overlap quarter by quarter. Or four ovals arranged in a ring. The inner curves align to form a round shape again. Creators sometimes enhance it with diamond or round gold leaf pieces (hana-shippō). Grids mixed in create the yotsume-shippō.

Fundō - Balance Weight Pattern

Fundō reflects the shape of scale weights. Curved lines meet in opposing pairs to mirror those old balance weights’ forms.

Manji - Swastika Motif

Manji has ancient roots in Japanese crests and textiles. It’s based on the Sanskrit swastika symbol. Variants include chained manjis, broken manji, or slanted versions called saaya-gata.

Yōraku - Beaded Ornament Pattern

Yōraku comes from Indian nobles’ bead and metal necklaces. Today, it shows up around bodhist statues’ necks or chests in paintings, giving a regal sense.

Patterns of Everyday Objects

Many kirikane designs mimic tools and objects. These include checkerboards, mesh grids, basket weaving, abacus sticks, interlocking rings, balance weights, and swastikas.

Pattern Creation Process

Crafting these designs begins with planning the motif: scale, tortoise shell, mesh, rings, or ornament. Artisans cut tiny gold, silver, or platinum leaf into precise shapes. Then they apply glue and set each piece by hand. It’s slow work. Every shape must fit exactly. And the light changes how each pattern looks. This change in sheen gives kirikane its allure.

Kirikane on Buddhist Statues: Where Gold Leaf and Sacred Art Meet

Kirikane doesn’t just live on scrolls or decorative crafts. It appears across Japan on historic Buddhist statues, especially from the Kamakura period. This gold-leaf art isn’t only beautiful. It holds deep spiritual meaning and gives each statue a sense of presence and life.

Tokyo’s National Treasures in Gold Leaf

At the Tokyo National Museum, you’ll find a standing statue of Monju Bosatsu from the Kamakura period, where kirikane adds detail and glow. There’s also a full group of Jūnishinshō statues, the Twelve Divine Generals. One of them, Inu-shin (Dog Guardian), has fine gold lines in the hair and a swastika pattern on its chest armor. Others like Mi-shin (Sheep), Tatsu-shin (Dragon), and Mi-shin (Snake) all carry unique kirikane elements. On the Snake Guardian, the hair uses fine linear kirikane, while the chest features the traditional basket-weave design called kagome.

Another Kamakura-period Bodhisattva statue in the collection shows multiple kirikane patterns. Its flowing robes display tatewaku curves, while the skirt includes designs like hemp leaf, lotus petals, sun rays, arabesques, and round flower emblems.

A dramatic statue of Monju Bosatsu riding a lion, created by Kōen, also uses kirikane and holds designated cultural status. The museum also displays an Amida Nyorai standing statue made by Eisai and an Aizen Myōō seated statue, both from the Kamakura period.

Sacred Works at Setagaya’s Kannōn-ji Temple

Setagaya’s Kannōn-ji Temple preserves a powerful set: the Fudō Myōō and the Eight Attendants, all from the Kamakura era and made by the sculptor Kōen. Each figure contains careful kirikane work that enhances its fierce, divine energy.

Kamakura-Era Gold Leaf in Kanagawa

In Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, the Jizō-dō at Gokuraku-ji Temple houses a standing Jizō Bodhisattva statue with kirikane ornamentation. At Tōkei-ji Temple, a statue of Seikanzeon Bosatsu from the Nanboku-chō period shows more fine detail, now held in the temple's treasure house. Shōmyō-ji Temple preserves a Miroku Bosatsu in its golden hall. During restoration, tools used for kirikane were found sealed inside this statue and are now stored at the Kanazawa Bunko Museum.

Chiba Prefecture’s Regional Cultural Assets

Eikō-ji Temple holds a Seiryō-ji-style Shakyamuni statue with kirikane on the chest and arms. It shows layered circles and floral scrolls. Another similar Seiryō-ji-style statue is kept at Shōgaku-in in Yachiyo City. This one is covered with tortoise shell and lattice-style gold leaf. Its condition is excellent, with minimal peeling.

Yamanashi and Fukui: Regional Masterpieces

Ryūen-ji Temple in Yamanashi preserves a seated Amida Nyorai statue from the Kamakura period. In Fukui, Nakayama-dera Temple houses a rare seated Batō Kannon statue. It features multiple kinds of kirikane: hail patterns, tortoise shell, seven treasures in gold, and square hail motifs in silver. The mix of gold and silver foil makes it a rare example of both beauty and craftsmanship.

Shiga Prefecture’s Long-Held Heritage

Ishiyama-dera Temple displays two wooden guardian kings from the Heian period. These figures are decorated with gold-leaf hail dots, hexagons, and shippō ring designs. Some sections even use silver foil or gold-silver blends.

Enryaku-ji Temple stores several significant works: a standing Amida Nyorai, a standing Seikanzeon from Yokogawa Chūdō Hall, and a Fudō Myōō. All are from the Heian or Kamakura periods and show strong kirikane detailing in robes and halos.

At Onjō-ji Temple, you’ll find a sitting statue of Shinra Myōjin from the Heian period. This figure is secret and only rarely displayed. Other works include a standing Eleven-Headed Kannon, a seated Fudō Myōō crafted by Moritada, and a relaxed statue of Hariti (Kariteimo) from the Kamakura period.

Shōjukuraigō-ji Temple holds a rare Muromachi-era pair of standing Nikkō and Gakkō Bosatsu figures, each with preserved kirikane.

Buddhist sculpture continues with Byakue Kannon seated in Baekje-ji and a Fudō Myōō with Bishamonten figure at Myōō-in, both showing kirikane accents.

Kyoto’s Statues and Gold Leaf Legacy

Kyoto, the heart of cultural tradition, holds more kirikane treasures. Gansen-ji Temple features a statue of Fugen Bosatsu riding an elephant from the Heian period. At Kurama-dera Temple, the holy treasure hall contains a standing Seikanzeon made by Higo Bettō Jōkei in the Kamakura era.

Kōryū-ji Temple’s lecture hall holds several key figures. These include seated statues of Jizō and Kokūzō Bosatsu, both crafted by Dōshō in the Heian period. The treasure hall also holds a rare standing Zaō Gongen, showing strength and divine authority.

These works prove that kirikane is more than a decorative style. It’s a sacred tradition, sealed into Japan’s most treasured statues. From Tokyo to Kyoto, each figure tells a story through its lines of gold.

Shōgakuin - Kamakura-Era Bishamonten Statue

At Shōgakuin’s Kannon Hall, the standing figure of Bishamonten from the Kamakura period is a designated cultural property of the prefecture. The armor’s front shield is decorated with the hemp leaf pattern (asanoha tsunagi), raised in gold mud pigment. It also features copper fittings. Together, these details capture the aesthetic tastes of late Kamakura craftsmanship.

Shōgoin - Heian-Era Fudō Myōō Statue

Inside the main hall stands a figure of Fudō Myōō from the Heian period. This piece is officially listed as an Important Cultural Property.

Jōruriji - Fudō Myōō and Four Heavenly Kings

The main hall at Jōruriji houses a standing Fudō Myōō with two child attendants, made using the joined-wood technique. It’s from the Kamakura period and is an Important Cultural Property. The same hall also contains two surviving figures from the original Four Heavenly Kings (Mochikokuten and Zōjōten), made in the Heian period and designated National Treasures. All four figures share matching hairstyles and costume types. Bright red, green, and gold pigments decorate the surfaces. Gold leaf motifs remain clearly visible, and their condition is remarkably preserved.

Jingōji - Bishamonten Hall

Here, the standing statue of Bishamonten dates back to the Heian period and is listed as an Important Cultural Property.

Seiryōji - Shakyamuni Buddha Statue

This Heian-period standing Buddha is a National Treasure. Known as the prototype for the "Seiryōji-style" Buddha, it features a unique hairstyle, mudrā (hand gesture), robe shape, and finishing techniques. Kirikane motifs of lotus and flowing water remain on the robes, and even the pleat tops show fine gold lines.

Daikakuji - Five Great Wisdom Kings

These statues were carved by Myōen using joined cypress wood. They are preserved as Important Cultural Properties.

Daigoji - Sanbōin Miroku Bosatsu

This seated Miroku Bodhisattva statue was created by Kaikei during the Kamakura period. It’s a rare example of gold mud coating and is also an Important Cultural Property.

Daihōonji - Ten Great Disciples

The standing figures of the Buddha’s ten disciples were carved by Kaikei in the Kamakura period. They’re recognized as Important Cultural Properties.

Tōji - Multi-Figure Buddhist Statues

Inside Tōji’s Niken Kannon hall, there are three Kamakura-period statues: Kannon Bodhisattva, Brahma (Bonten), and Indra (Taishakuten). The figures have soft touches of color on the hair, eyebrows, eyes, lips, and beards. Their garments feature a wide range of kirikane patterns, including running stream (tatewaku), hemp leaf, slanted grids, fish scales, arabesques, tortoiseshells, four-circle shippō, and round floral designs. These intricate gold patterns brighten the entire surface. The statues have been well preserved inside a shrine case, with almost no flaking.

In the same temple, the seated Fudō Myōō in the Mikagedō Hall is a hidden Heian-era Buddha and a National Treasure.

Ninnaji - Yakushi Nyorai and Aizen Myōō

The Yakushi Nyorai (Healing Buddha) is a small white sandalwood figure just 11 cm tall, stored in the Reimyōden. It’s from the Heian period, made by Ensei and Chōen, and considered a hidden Buddha and National Treasure. The halo includes attendant figures of the Sunlight and Moonlight Bodhisattvas and seven Yakushi Buddhas, while the base displays all Twelve Heavenly Generals. Gold motifs like four-circle shippō and running stream patterns decorate the robe, halo, and pedestal. Since it was hidden for centuries, the gold patterns are still well preserved.

Another notable piece at Ninnaji’s Reihōkan is a seated Aizen Myōō made of cypress, from the Heian period and listed as an Important Cultural Property.

Byōdōin - Eleven-Faced Kannon

The Hōshōkan museum holds an Eleven-Faced Kannon Bodhisattva from the Heian era. Once the main statue in the Kannon Hall, it’s now preserved as an Important Cultural Property.

Bucchōji (Mineji) - Thousand-Armed Kannon

This seated figure of the Thousand-Armed Kannon, carved from cherry wood in the Heian period, is an Important Cultural Property. The robes show detailed kirikane designs such as running stream, shippō, and tortoiseshell patterns. The pedestal’s lotus base and arch feature hail-dot motifs. The base frame includes a four-circle shippō pattern. These elements reflect the refined Buddhist statuary style at the end of the Fujiwara era.

Also in the main hall are standing statues of Fudō Myōō, two child attendants, and Bishamonten, all from the Heian period and preserved as Important Cultural Properties. The Fudō Myōō figure has flowing ink-like surface patterns. Kinkara Dōji (the right attendant) wears a grass-eating bird design, while Seitaka Dōji (the left) features floral branch motifs - rare examples in Buddhist sculpture.

Hōkaiji - Twelve Heavenly Generals

These standing statues from the Kamakura period are designated Important Cultural Properties.

Hōkongōin - Eleven-Faced Kannon

A seated Eleven-Faced Kannon Bodhisattva statue from the Kamakura period is kept here. It was crafted by Inryū and Inyoshi and is recognized as an Important Cultural Property.

Mimurotoji - Shakyamuni Buddha

In the temple’s treasure hall is a Heian-period standing statue of Shakyamuni Buddha, classified as an Important Cultural Property.

Myōhōin - Sanjūsangendō

This hall houses 28 guardian deities carved in the Kamakura period using the joined-wood method. The group is designated a National Treasure.

Rokuonji (Kinkakuji) - Portraits of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu and Buddhist Statues

On the first floor is a statue of the third shōgun, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, made in the Shōwa era by Matsuhisa Sōrin and Matsuhisa Masaya. On the second floor are images of Iwaya Kannon and the Four Heavenly Kings, also from the Shōwa period, by the same sculptors.

Rokuharamitsuji - Jizō Bodhisattva Statues

The treasure hall preserves two Heian-period Jizō statues. One is the standing “Katsura-wearing Jizō,” and the other is the seated “Dreaming Jizō,” which is traditionally attributed to Unkei. Both are protected as Important Cultural Properties.

Notable Kirikane Buddhist Sculptures in the Kansai Region

In Nara Prefecture, the Nara National Museum holds an important lion statue from the Heian to Kamakura period. This lion once carried the Bodhisattva Monju. Its mane shows traces of verdigris green coloring and fine gold-leaf linework.

There’s also a standing statue of the Eleven-Headed Kannon from the Kamakura period. A standing Jizō Bodhisattva and a seated Nyoirin Kannon from the same era are also preserved. The robes on these figures display patterns like diagonal lattices, floral motifs, hemp-leaf designs, and circular floral emblems created with thin gold lines.

A seated statue of Aizen Myōō from the Kamakura period shows similar detail and is listed as an Important Cultural Property.

At Akishino-dera, the main image of Daimotsu Myōō in the Great Hall is another Kamakura-period work. Though much of the gold leaf detailing in the hair has worn off, you can still see its original striped technique in places.

Abe Monju-in holds a rare Kamakura-period set called the Five Great Monju, sculpted by Kaikei. Each figure is designated as an Important Cultural Property.

Eizan-ji houses a set of Twelve Heavenly Generals from the Muromachi period, also officially protected.

In Ikoma City’s Enshō-ji, a seated Shaka Nyorai statue shows off traditional joined-wood construction from the Kamakura period. It sits in lotus position, with hands forming the gestures of fearlessness and wish-granting. Gold mud covers the body. On the robes, patterns of interlinked swastikas, overlapping rings, and hemp-leaf lattice are carefully applied in gold leaf.

Kōfuku-ji Temple has multiple works of note. In the East Golden Hall, the standing Four Heavenly Kings from the Heian period are made of single blocks of cypress. These statues are National Treasures. That same hall also holds a Kamakura-period set of Twelve Heavenly Generals made by Shūami and others. The Middle Hall has more Four Heavenly Kings from the same era, made with joined wood. The National Treasure Museum at Kōfuku-ji keeps a set of Twelve Heavenly Generals in flat relief from the Heian period.

At Saidai-ji, the main hall contains a standing Shaka Nyorai statue made in the Kamakura period in the Seiryō-ji style by Zenkei and others. The Five Monju statues there are also Kamakura works. In the Aizen Hall, a seated statue of Aizen Myōō by Zen'en shows lined hair detail and wave-style kirikane designs on the robes. All are classified as Important Cultural Properties.

Shōryaku-ji temple preserves a seated Kujaku Myōō from the Kamakura period, registered as a Cultural Property by Nara Prefecture.

Chōkyū-ji’s main hall has a standing Eleven-Headed Kannon Bodhisattva from the Heian era. It too is protected as an Important Cultural Property.

At Tōshōdai-ji, the worship hall keeps a hidden seated statue of Shaka Nyorai from the Kamakura period in the Seiryō-ji style.

Tōdai-ji houses many masterworks. The Junshedō contains a standing Amida Nyorai made by Kaikei during his period as An-Amida. It shows kirikane work like ring chains, four-eyed tortoiseshell, double diagonal grids, basket weaves, and other refined patterns. The Hokke-dō holds standing statues of Nikkō and Gakkō Bodhisattvas from the Nara period, both National Treasures. In the Kanjin Hall, a standing Jizō Bodhisattva made by Kaikei during his Hōkyō period features a delicate face and flowing robes. It rests on a lotus pedestal over white clouds, with gold line motifs still intact.

Nyoiin-ji keeps a standing Zaō Gongen from the Kamakura period, made by Genkei, also listed as an Important Cultural Property.

At Hannya-ji, a Monju Bodhisattva riding a lion is a Kamakura-period work by Kōshun and Kōsei, also protected.

Byakugō-ji owns a standing Jizō Bodhisattva from the same era.

Futai-ji preserves a complete set of Five Great Myōō figures from the Heian period: Fudō Myōō, Gōzanze Myōō, Daiitoku Myōō, Gundari Myōō, and Kongōyasha Myōō. All are recognized as Important Cultural Properties.

At Hōzan-ji, the main hall holds a standing Fudō Myōō statue and an image of Butsugen Butsumo from the Edo period. These statues show a wide range of kirikane patterns: thunder swirls, wave designs, arabesques, basket weaves, diagonal grids, and various modified swastika patterns including the classic sayagata. Silver-leaf kirikane is used as well, and preservation remains excellent.

In Hōryū-ji’s Daihōzōin, the seated Nyoirin Kannon made of a single block comes from Tang China and is an Important Cultural Property. In Denpōdō Hall, statues of Brahma and Indra stand from the Heian era, though not on public display. In the Golden Hall, figures of Bishamonten and Kisshōten from the Heian period are National Treasures, as are the Four Heavenly Kings from the Asuka period, the oldest known in Japan. They were made by Yamaguchi Ōguchi Hitori. The Upper Hall contains another Four Heavenly Kings set from the Muromachi period. In the Shōryō-in, seated figures of Prince Shōtoku, Prince Yamashiro, Prince Eguri, Prince Sotsumuro, and the monk Eji from the Heian period are all National Treasures.

Notable Kirikane Statues Outside Nara

In Osaka Prefecture, Kanshin-ji’s Reihōkan Hall houses a seated Aizen Myōō statue from the Kamakura period. It is designated an Important Cultural Property.

Kōon-ji keeps several Heian-period works in its treasure hall: a standing Monju Bodhisattva and a standing Nanda Ryūō, both officially protected.

In Wakayama

The Konjō Zanmai-in temple also preserves significant statues, though further detail is not included in this record.

Kongō Sanmaiin: Tahōtō Pagoda with Seated Five Wisdom Buddhas

The grand Tahōtō pagoda at Kongō Sanmaiin holds the secret seated statues of the Five Wisdom Buddhas. They date to the Kamakura period. This sacred space is recognized as an Important Cultural Property. The Buddhas sit in meditative calm, embodying profound wisdom and serene power.

Kongōbu‑ji Temple

Inside Kongōbu‑ji’s treasure hall is a standing image of Fudō Myō‑ō. It was crafted during the Heian period and preserves a weighty presence. This statue, too, enjoys Important Cultural Property status. Each aspect of the figure reflects dedication and spiritual depth.

Treasure Hall’s Seated Peacock Myō‑ō by Kōkei

Also housed in the hall is the seated Peacock Myō‑ō. It was made by the master sculptor Kōkei during the Kamakura era. The statue is ornate and moves viewers with its divine bearing. It is another officially protected Cultural Property.

Kōdai‑in Temple: Kamakura Amida Triad by Kōkei

At Kōdai‑in, you’ll find a Kamakura-era standing triad of Amida Buddha sculpted by Kōkei once more. The figures glow with precise detail and spiritual focus. This piece, too, carries an Important Cultural Property designation.

Jōki‑in Temple: Seated Jizō Bosatsu from the Kamakura Period

Jōki‑in enshrines a serene seated Jizō Bosatsu from the Kamakura era. It is the work of Inshū‑tō, steeped in simple grace. The statue reflects solace and guardianship, quietly honored as a cultural treasure.

Buddhist Paintings with Kirikane at the Tokyo National Museum

The Tokyo National Museum houses several ritual Buddhist paintings using kirikane gold leaf. The first is a seated Jundei Kannon from the Heian period, also an Important Cultural Property. It centers on the Jundei Mandala, surrounded by the Four Heavenly Kings, used in esoteric rites for warding off misfortune or praying for children.

Also in the collection is a Heian-period Thousand-Armed Kannon, a National Treasure. It features 11 small faces and 21 large arms on each side, flanked by Merit Devas and Vasubaddha Devas.

The Kokūzō Bosatsu painting from the Heian era, another National Treasure, displays muted tones with silver ink and silver-leaf kirikane adorning the surface.

The Peacock Myō‑ō from the Heian period, also a National Treasure, is shown with four arms in vibrant color and delicate kirikane patterns. It symbolizes divine protection against snakes and pests.

Works at the Kyoto National Museum

The Kyoto National Museum preserves several Heian-period National Treasures. One shows the Buddha emerging from his golden coffin, preaching and greeting his mother Maya. Another piece is a twelve-deity set representing elemental and heavenly guardians such as Fire Heaven, Wind Heaven, Indra, and Brahma. These images are richly decorated with kirikane patterns like jewel-linked, cross-linked swastikas, wavy motifs, and diagonal grids.

Pieces at the Nara National Museum

In Nara, the museum holds two mandalas from the Heian era with Important Cultural Property status. The first features Dainichi in the one-character gold wheel mandala, seated on a lion throne with fire-flame halo. The ornaments are embellished with metal foil. The second is the Great Buddha Peak mandala, showing Dainichi with sun disk above Mount Sumeru, with intricate kirikane patterns on the robes. This piece is notable for its rare use of silver-leaf on the Buddha face.

The museum also holds a Kamakura-period Thousand-Armed Kannon with 42 arms and 11 faces, seated on a lotus rock, blending into a natural setting. A Kamakura-era Nyoirin Kannon sits with right knee raised on a lotus seat, wrapped in moonlight halo and layered in gold ground with kirikane patterns like wavy lines, grids and broken swastikas.

An Heian-era Eleven-Faced Kannon National Treasure sits on a white lotus, hand in wish-granting pose, wrist adorned with prayer beads, left hand holding a lotus-tipped vase.

The Heian-era Samantabhadra Bodhisattva, an Important Cultural Property, is painted in soft hues with kirikane curves on the robes and a full-body necklace of linked gold and silver cut-foil.

There is also a Heian-era Pure Land mandala of Amida, rich in warm color with red outlines and metal-foil ornaments, protected as an Important Cultural Property.

Lastly, a Kamakura-period Jizō Bosatsu is seated amid a mountain landscape, its robes detailed with delicate kirikane.

Treasures of Jingo‑ji Temple, Kyoto

At Jingo‑ji in Kyoto, the National Treasure statue of Shakyamuni emerges in serene pose. The robes show jewel-linked kirikane motifs, linking heart and tradition through metal leaf.

Ryūkō‑in in Wakayama: The Miraculous Vessel Kannon

At Ryūkō‑in, there is a rare painting called “Vessel of the Manifested Kannon at Sea.” It tells the legend of Kōbō Daishi’s ship caught in a storm, where Kannon appeared onboard. The work is richly colored in gold and overlaid with kirikane patterns like wavy lines, four-eye jewel, and broken swastika designs.

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, USA

Several of these cultural and artistic treasures are also preserved overseas in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Heian-Era Buddhist Artworks in the Guimet Museum, France

The Guimet Museum in France holds several rare Buddhist paintings from the mid-12th century Heian period. One is a depiction of Batō Kannon, the Horse-Headed Avalokiteśvara, known for protecting beings with fierce compassion. Another is a portrait of Samantabhadra Enmei Bosatsu, tied to long life and esoteric rituals. A third is the seated Nyoirin Kannon, the Wish-Fulfilling Avalokiteśvara, who is often shown in a relaxed posture yet radiates quiet power. These pieces carry the soft, spiritual presence unique to Heian religious art.

Tang Dynasty Buddhist Images from China

Also in the Guimet collection is a 9th-century Tang dynasty image of an itinerant monk walking with a tiger. It captures a strong symbolic moment of harmony between nature and spiritual pursuit. Another is a later 9th-century statue of Yakushi Nyorai, the Healing Buddha, flanked by two monk-like attendants. These works reflect Chinese interpretations of Buddhist iconography just before the Five Dynasties period.

A 10th-century seated Kannon of Salvation surrounded by attendants also shows the rich detail and layered meaning that defined Buddhist devotional art in late-Tang China.

Tokyo National Museum Holdings

The Tokyo National Museum houses multiple standout pieces. These include several versions of the Thousand-Armed Kannon, the Jundei Kannon, and the Kokūzō Bosatsu. Each figure has its own spiritual purpose but shares traits like serene facial expression, multi-layered robes, and the intricate use of gold-leaf kirikane.

The museum also keeps a stunning depiction of the Peacock Myō‑ō. The color, symbolism, and ornamental technique combine to produce something both protective and refined. Every line has purpose, every glow reflects centuries of devotion.

Kyoto National Museum Buddhist Treasures

At the Kyoto National Museum, the Shakyamuni Emerging from the Golden Coffin scene stands out. The Buddha is seen rising from his own coffin to speak, greeted by his mother Maya. The expression is calm, but the message is intense - teaching continues even after death.

Among the museum’s Twelve Heavenly Deities, one figure of Water Deva (Suiten) stands out for its cool expression and flowing motion. All twelve are rendered with kirikane patterns like interlocked swastikas, wave motifs, and jewel-link borders.

Nara National Museum Collections

Nara’s museum houses some of the most refined Buddhist art in Japan. The One-Syllable Gold-Wheel Mandala shows Dainichi Nyorai sitting on a lion throne, flame halo behind, body adorned in fine foil detailing.

Another is the Great Buddha Peak Mandala. Dainichi is shown meditating over Mount Sumeru, sun disk on his back. The robes shimmer with linked treasure motifs and precision patterns. This painting even uses silver-leaf kirikane, which is rarely found in Buddhist imagery.

The Eleven-Faced Kannon from the same museum sits atop a lotus, one hand raised in blessing, another holding a vase with a blooming red lotus. Every detail reinforces balance and compassion.

Also there is a painting of Nyoirin Kannon surrounded by golden moonlight, seated casually but fully alert. Kirikane detailing covers the robes, seat, and halo, woven tightly into the imagery.

The painting of Samantabhadra (Fugen Bosatsu) wraps the figure in faint colors, then outlines every fold of the robe in gold and silver foil. Necklaces and jewelry stretch across the entire body.

Their depiction of Jizō Bosatsu sits quietly within a mountain setting, the robes lined with fine kirikane detail. The whole image merges natural landscape and sacred presence.

Treasures of Kyoto’s Jingo‑ji and Wakayama’s Ryūkō‑in

Jingo‑ji Temple in Kyoto holds a National Treasure image of Shakyamuni sitting alone in full lotus posture. His robes shine with jewel-linked kirikane motifs, simple yet deeply moving.

At Ryūkō‑in in Wakayama, there is a painting of Kannon appearing aboard a ship during a storm. This story says Kūkai (Kōbō Daishi) saw the Bodhisattva arise from the sea during a Tang-era voyage to China. The painting is rare. The surface is painted in gold over layers of kirikane with wavy lines, broken swastikas, and four-eye treasure motifs.

Boston Museum of Fine Arts: Preserving Japanese Icons Abroad

In the United States, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston also holds important examples. These include a Batō Kannon image from the Heian period and a portrait of Samantabhadra Enmei Bosatsu, both dating to the 12th century. Their survival overseas shows just how far Japanese Buddhist art has traveled and how valued it remains globally.

Living National Treasures: Protecting Kirikane for the Future

Only three people have ever been named Holders of Important Intangible Cultural Heritage for kirikane...

The first was Saita Baitei, born in 1900, who received the title in 1981. He passed away that same year.

The second was Nishide Daizō, born in 1913, who earned the honor in 1985. His influence shaped modern kirikane. He died in 1995.

The third is Eri Sayoko, born in 1945. She was recognized in 2002 and passed away in 2007. Her work carried the tradition into the 21st century.

These three names define the heart of kirikane. Their skills preserved it, and their dedication passed it down.