Byzantine Glass

By the fourth and early fifth centuries CE, glass objects in the Byzantine realm closely mirrored earlier Hellenistic vessels in both design and purpose. In the fifth century CE, glass artisans primarily in Syria and Palestine began crafting a unique Byzantine glass style. They continued to make vessels for pouring and drinking, but also expanded into creating glassware for lighting, currency and commodity weights, window panes, and mosaic and enamel tesserae.

Rise of Glassware in the Byzantine Period

Glass becomes more than just tableware. Glass lamps and lighting vessels become widespread, while glass weights serve economic functions. Window glass grows in use, bringing natural light into buildings. Glass tesserae gain popularity, adding color to mosaics and enamel artworks.

Byzantine Glass After the Arab Conquests

After the Arab conquests in the seventh century CE, the Levant remained a key source of both raw and finished glass. Glass continued to be imported from this region. Archaeological digs have revealed many plain glass items in modest households. This counters earlier assumptions that glassware was only a luxury for the wealthy.

Composition of Byzantine Glass

Chemical tests show Byzantine glass used the same core ingredients as Roman glass. Sand sourced silica, mixed with a flux and lime, formed the base. Artisans added different coloring agents for visual effects.

Glass-Making Techniques in the Byzantine Era

Glass production carried on the two-stage Roman method. The first stage was primary glass-making: raw glass created from sand and stabilizer. The second stage was secondary glass-making: reheating and shaping raw glass into items. While archaeologists readily locate primary glass manufacturing sites, workshops for secondary production are far harder to identify.

Archaeological Glass Factories in the Byzantine World

The Early Byzantine era saw glass production centers across Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. Archaeologists have also found factories in Greece, including Corinth and Thessaloniki, and in Asia Minor. Chemical analysis of sixth-century glass weights shows production in Carthage and along the Danube River. Textual sources also mention glassmaking hubs in Constantinople, Emesa (modern Homs in Syria), and various towns across Egypt.

Who Made Byzantine Glass

Glass-makers worked as independent artisans, not under guilds in most towns. Some communities did form glass-maker guilds. Both men and women took up glass-making. A surviving contract from Armenia refers to a woman glass manufacturer, proving female involvement in the craft.

Shapes and Styles of Byzantine Glass Vessels

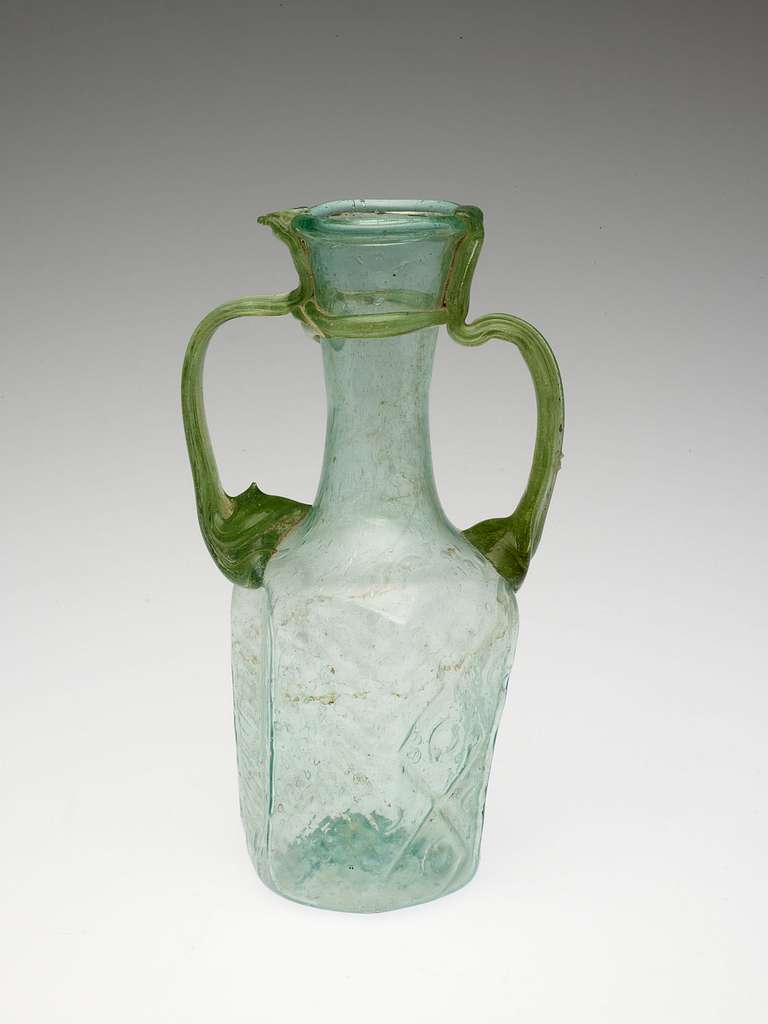

Shapes of glass vessels in the Byzantine period stayed similar to those from the high Roman era. From the late fifth century, Near Eastern glassblowers began crafting larger vessels. They introduced a folded, stemmed foot design. In the sixth and seventh centuries, vessels often have a delicate u-shaped mouth. By the fifth century, some classical Roman glass shapes went out of style. These include bowls, flat-bottomed cups and beakers, and footed wine jugs with trefoil mouths.

Byzantine Glass Lamps

During the Byzantine era, glass lamp technology emerged as a game changer. The first glass lamps appear in the early fourth century CE in Palestine. They quickly surpassed clay lamps in efficiency and popularity. By the mid-fifth century CE, glass lamps were spreading rapidly across the Byzantine world toward the west. At first, these lamps resembled ordinary drinking vessels. Yet, over the sixth and seventh centuries, this basic shape evolved into seventeen distinct forms, each designed for varying uses and aesthetics.

Enamel Relief Icons after the Triumph of Orthodoxy

In 843 CE, the Triumph of Orthodoxy marked a turning point in Byzantine art. Enamel relief icons rose to prominence as the preferred medium of religious imagery. A prime example is the enamel depiction of Michael the Archangel, now housed in St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. This form of icon quickly dominated Byzantine religious art, shaping devotional practices and artistic trends.

Adoption of Silver-Staining Techniques

By the middle Byzantine period, glassmakers in Byzantium began using silver-staining techniques learned from the Arab world. The process involved coating glass surfaces with a metallic compound mixed with a clay or ochre base. The glass was then fired at a temperature just below its softening point. This heat triggered a chemical reaction that embedded the stain into the glass, creating a range of colors determined by the compound’s recipe.

Although Arab artisans in Egypt began silver-staining glass in the late eighth century, the earliest Byzantine example dates to the ninth century. This method gained popularity, especially in making simple glass bracelets. These bracelets, dating between the tenth and thirteenth centuries, spread widely across Byzantine territories, from Greece to Anatolia. The most celebrated Byzantine silver-stained object is the interior inscription on the San Marco glass bowl, which dates to the Macedonian Renaissance in the tenth century.

Fragments of silver-stained window glass have also been found, though such works were less common in Byzantium than they later became in late medieval Europe. Nonetheless, Byzantine practice of silver-staining likely helped bridge this technique from the Arab world to Western Europe.